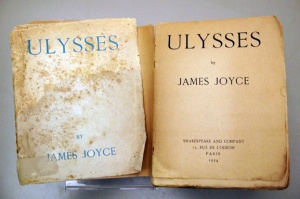

These last few days I’ve had Joyce in my mind. No great surprises here: after all he is never far from you if you live in Dublin. And I did write my Ph.D. thesis on Ulysses. And it was the centenary of the publication of Dubliners yesterday and it is Bloomsday today. But I want to write about him because sometimes he gets lost in the big theme park that is Dublin around the 16th of June. Amidst the boaters, the lace camisoles, and the ashplants of fake Edwardiana, we lose sight of the hardwork and dogged dedication of the man who conjured up the lowly, tedious, exhalting, onanistic, fetishistic, scatological, lyrical, intellectual and cod-intellectual, poisonously funny, orgiastic, combative, melancholic, phantasmagorical, exhausting, compassionate and exhilarating book that is Ulysses.

Ulysses is all of the above yet impossible to define or exhaust. It is hard to believe it came in the heels of Dubliners, a collection of lean short stories that kicks ass from here to kingdom come. Put them together and you have the Classic and the Baroque; “scrupulous meanness” and unending largesse; feast and famine. You may just say that with both books we have a universe spinning on the tip of Joyce’s slender elegant fingers.

Ulysses is all of the above yet impossible to define or exhaust. It is hard to believe it came in the heels of Dubliners, a collection of lean short stories that kicks ass from here to kingdom come. Put them together and you have the Classic and the Baroque; “scrupulous meanness” and unending largesse; feast and famine. You may just say that with both books we have a universe spinning on the tip of Joyce’s slender elegant fingers.

And Joyce was a slender man. A lean body punctuated by languidly ironic eyes magnified by his spectacles. Joyce was partially sighted and maybe that explains why he seems to look through the viewer when you stand before one of his portraits. His short sightedness may account for the splendid arrangements of people and objects in his prose. His mastery of space and movement, of the relative position of objects and characters may very well be connected to his disability, to the need of the increasingly blind man to register everything and everyone, as Will Self has suggested. Like Self, I do believe that Joyce’s impaired sight played an important part in the fashioning of his talent, from the stunning mastery of space as remembered and re-arranged, to the nostalgia that fastened him to the Dublin of his youth, through to the increased musicality of his work and then on to the darkest night of the dream in Finnegans Wake. The last story in Dubliners, “The Dead” offers the most precise arrangement of food on a table I have come across in my readings:

A fat brown goose lay at one end of the table and at the other end, on a bed of creased paper strewn with sprigs of parsley, lay a great ham, stripped of its outer skin and peppered over with crust crumbs, a neat paper frill round its shin and beside this was a round of spiced beef. Between these rival ends ran parallel lines of side-dishes: two little minsters of jelly, red and yellow; a shallow dish full of blocks of blancmange and red jam, a large green leaf-shaped dish with a stalk-shaped handle, on which lay bunches of purple raisins and peeled almonds, a companion dish on which lay a solid rectangle of Smyrna figs, a dish of custard topped with grated nutmeg, a small bowl full of chocolates and sweets wrapped in gold and silver papers and a glass vase in which stood some tall celery stalks. In the centre of the table there stood, as sentries to a fruit-stand which upheld a pyramid of oranges and American apples, two squat old-fashioned decanters of cut glass, one containing port and the other dark sherry. On the closed square piano a pudding in a huge yellow dish lay in waiting and behind it were three squads of bottles of stout and ale and minerals, drawn up according to the colours of their uniforms, the first two black, with brown and red labels, the third and smallest squad white, with transverse green sashes.

Of course, given the slant of this blog, I wanted to pick food-centred passages to illustrate my observations but the above is exemplary of Joyce’s extraordinary control as a writer, even the unpublished writer in his twenties he was when he wrote this. There is nothing in the description of the Misses Morkans’ table that can be attributed to a desire to impress the reader with literary know how: there are no unnecessary metaphors or flights of expressive fancy. What there is, however, is an iron-willed commitment to transporting the reader to the table right before the momentous dinner commences. It seems appropriate that the effort should finish with military imagery to describe the arrangement of the bottles; in fact, Joyce, like a gifted strategist, displays military precision in his description of the food at the party.

All the details are here for us to be awash with the muificence and hospitality of Gabriel’s aunts; to be touched by a generosity that has been hard earned on their part; to feel a tinge of shame at Gabriel’s earlier (private and unvoiced) disparagement of his aunts and their guests as he mentally reviewed the notes for his after dinner speech. That is, Joyce, here as elsewhere in Dubliners, is giving us an “objective” account in which to contextualise Gabriel’s subjectivity, a technique he consistently exhibits throughout Dubliners to remind us that his characters are at once individual and exemplary.

But the Misses Morkans’ table is also a detailed cypher of a culture that Joyce sees as disappearing: the wonderful colourful and enticing foodstuff that will fall into the stomachs of those who are nearing their shadowlands. Life transitioning into death. An old Ireland in the throes of a shocking transformation, perhaps echoed in Gabriel’s own “epiphany” at the end of the story. To read the above passage is also to understand the laxity and tiredness that washes over Gabriel’s wife, Gretta, towards the end of the story and how the relaxed body may be awaken to its spiritual past in the lull of the afterdinner wind down.

In Ulysses, the material debris of life becomes the portal to Leopold Bloom’s consciousness, a sensualist that reflects Joyce’s own increasing immersion in living life bodily. Leopold Bloom, unlike his touchingly ponderous and pretentious counterpart, Stephen Dedalus, uses sensation as a springboard to meditation. Joyce chooses to present him engaged in his morning routine, getting his wife’s breakfast ready:

Mr Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liverslices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hencods’ roes. Most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.

Kidneys were in his mind as he moved about the kitchen softly, righting her breakfast things on the humpy tray. Gelid light and air were in the kitchen but out of doors gentle summer morning everywhere. Made him feel a bit peckish.

The coals were reddening.

Another slice of bread and butter: three, four: right. She didn’t like her plate full. Right. He turned from the tray, lifted the kettle off the hob and set it sideways on the fire. It sat there, dull and squat, its spout stuck out. Cup of tea soon. Good. Mouth dry. The cat walked stiffly round a leg of the table with tail on high.

Apart from being a strikingly euphonic phrase, characteristically couching lowly earthy life in music, “the fine tang of faintly scented urine” is an appropriate ticket to the journey the reader spends in Bloom’s company. There is much talk in our culture of mindfulness and authenticity, but if you want to see their artistic rendition, you should look no further than Bloom: his alertness to the world as it unfolds is all encompassing and unprejudiced. Remember that when you step out onto Georgian Dublin and somebody suggests you go for a Bloomsday breakfast. This is not a day for crumpets and tea sipped in Edwardian regalia: Joyce filtered his universe through the warm entrails of life.

Go on, it is time to take off the boater and open the book.