Sitting outdoors watching the world go by in a foreign capital in the summer time, a beer glass is a shield and a bridge. As a shield it guards against thirst and heat, but it also represents enough ease with the alien culture to keep the outside world at bay. Like a bridge it also suggests the beckoning of belonging, a short stroll towards our neighbours, seen through the clear glass and amber gold.

Tag Archives: Beer

Still Lifes: Vilnius and Dagauvpils

The straight and narrow

As a Madridian living in Dublin I am often asked to sum up my city by prospective Irish visitors. I have long maintained that Barcelona, prosperous, outward looking, idiosyncratic but cosmopolitan, is the real capital of Spain. It seems to me that tourists don’t feel they need to ask about Barcelona because Barcelona, like all other great cities of the world, already has its own legend. I don’t imagine Parisians get asked what Paris is like, simply because it does not matter what it is like, what matters is what visitors imagine it to be. They will measure their experience against a dream they have had for years.

Madrid is something else, something darker and truly unknown beats at its centre: it may be the heart of everything that is in the shadows of Spain, like Barcelona is at the heart of everything that is bursting with light and sea and colour. Or not. It may not be quite as romantic as that, it could be that it is a geopolitical curiosity, even absurdity: plucked out of the shade to become the capital because of its literal centrality. Madrid is a riverless sealess hamlet that happened to be at the bull’s-eye of a growing empire; a grande dame born out of an undernourished grubby urchin.

Of course I never say these things to those who ask me about my home city. It would not be helpful. I may ask them if they like art, what kind of food they enjoy eating, would they like to take a day trip. What I really would like to say, if anybody asked me to help them understand Madrid is that for some reason, its inhabitants are drawn to narrow watering holes heaving with raucous bodies who standing side by side seem to relish the confusion.

The last time I was in Madrid I was struck by this undeniable fact of life there. Two days short of New Years Eve I am walking towards a night out in my favourite neighbourhood, Lavapiés, home to misfits and martyrs of all colours and creeds. Going up Calle Carretas, skipping up and down the footpath to avoid fellow pedestrians blinded by the urgency of their Christmas shopping, I look left and I see a long and tight pastry shop specialising in croissants with fillings. It is chock-a- block with punters, and the very discomfort it showcases, the narrow proximity of the clientele, seems to act as a centripetal force. Earlier, before I reached Sol, I had a glimpse of the venerable Casa Labra, driving punters in droves to taste its famed buñuelos de bacalao (cod croquettes). The croissant place and Casa Labra could not be more different, one, garishly lit and anodyne, the other, glowing with wooden warmth. Never mind that Casa Labra is a historical treasure and croissantplace will be replaced with another flavour-of-the-day establishment in less than a year. They are both integral to the experience of being in the city I was born in because what matters is that they were created following an individual’s initiative and that that same individual (or their successors as in Casa Labra) furnished it and runs it according to their taste and potential (creative, culinary, musical and, of course, financial).

Living abroad helps you understand your city much better, of course, one day you go over and you see it afresh, as if finally fitted with the lenses that allow you to see beyond your provincial short sightedness. Dubliners have very different drinking habits to Madridians and they often register alarm at the notion that you will only have one drink in a bar before moving on to the next one as we do there. The Irish act as birds of prey when they walk into a busy pub: they crane their necks and, on spotting an opening, mercilessly descend on a free table. They will sit there for the night, marinating their conversation in the same spirits that pickle their livers, and I should know because I am as much of a bar hawk here as the next one. By contrast eating and drinking in Madrid is a restless and nomadic experience. It partly has to do with the weather, which allows for freer rambling without battling against wind or rain, and with the lengthened nature of nights in Spain, which stretches them way beyond the Irish bedtime. But the third vortex of the, ahem, Barmuda triangle I am tracing here is the individuality I offered above.

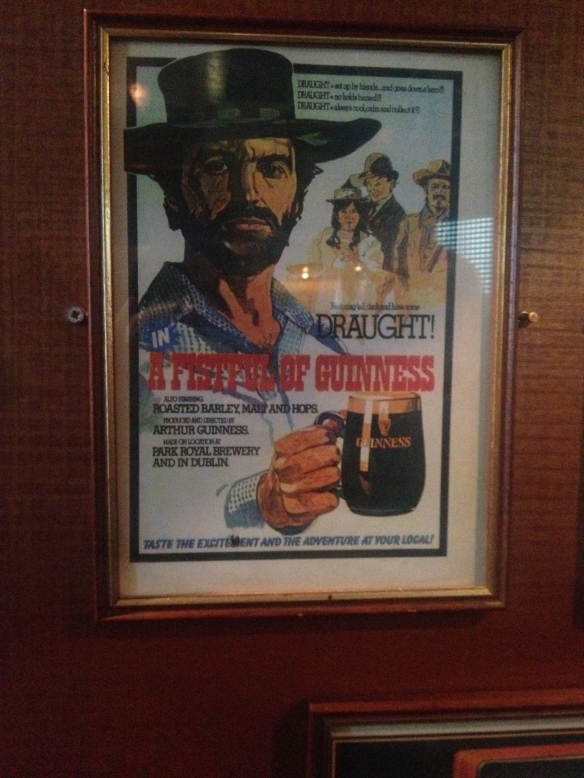

I don’t suggest that Irish pubs are without character, they can have it in spades, but the differences are subtle and, when it comes to drink or food, with the exception of recently introduced hipster gastro pubs offering speciality beers and fashioned to some tried and tasted business model, they all offer the same range of beers and mediocre wines. As for food, nobody is going to cross the road to get dry roasted peanuts instead of ready salted. The choice is simple for me, when it comes to pubs, old is better than new, mixed clientele a must, good Guinness (for its quality does change from pub to pub) and company I will be happy to spend many hours with. Ah, Madrid, I cannot pin it down so easily. In Dublin I cherish variations of the same evening, a discrete change in volume or tone, a harsher or sweeter finish, make for the differences in my memory. I just never had the same night twice in Madrid. The one I offer now is a vignette, not an emblem.

We rove freely up and down the narrow streets of Lavapiés, dropping a friend and picking two more on the way. Somebody remembers a Gallego tavern from the weekend before but it is full at this time, so we cross the road to get an aperitivo, Vermouth for me, in a good bodega across the road. A couple of tapas will tie us over until the Gallego frees up some space. After dinner, somebody suggests a stiff drink in a hole-in-the-wall run by a crank whose idea of décor are prints of topless beauties painted in the eighties pastel palette of the Athena school (of posters, not classical art). They would not be out of place in the villain’s den in an old episode of Miami Vice. There is an overpowering smell of disinfectant covering up a multitude of sins, and a whiff of what is summed up as some intractable electric malfunction by the owner lingers in the air. Pointing at a stitch above his eyebrow the publican tells us that he had a “friendly encounter” with the floor the previous night and laughs it off. As we leave to get a chaser in another bar two roads down, he is returning a fully charged smartphone to a languid beauty in her early twenties, as out of place in this eighties time capsule as her new iPhone 5.

The next bar is dark and loud and furnished with what look like motley findings in the nearby Sunday flea market of El Rastro. It is squarely below zero outside but for some reason a solitary Brazilian has seen it fit to leave his hotel in a pair of sooty havainana flip flops to nurse a red wine here. The red wine would give him away as a foreigner even if he was appropriately dressed for the dry piercing cold, no native would drink wine without food, especially not in a bar that is clearly a place to down a bottle of beer or a gin and tonic before moving on. We will cross paths with our Brazilian friend later, and draw him to El Calvario, a place that offers live music and ramshackle and blasphemous décor with your drink. There a homeless man in his sixties, will sit silently by the wall across from me and then ask for a cigarette as two of my friends hotly debate the state of the Spanish left, oblivious to this man’s disappointment when I say I don’t smoke and to the ravenous way he eats the bocadillo he produces out of a plastic bag stuffed in his pocket: a sausage drowning in ketchup and mustard rapidly disappears before he does.

I spot him again in Candela, the two tier flamenco bar in Calle del Olivar: the basement is where flamenco musicians are said to jam into the wee hours some nights and access is by invitation only; the main bar, an equal opportunities late bar, welcomes the high and dry that waft in through its doors after all other bars have shut for the night. The homeless man I saw in Calvario is also tolerated, even welcomed, here, and he sits by the cigarette machine, perhaps hoping to catch a punter who will not be able to deny the evidence when he tries to bum a fag. A friend and I begin to dance: a loving parody of the flamenco moves whose vigour and grace we could never approximate. On the stage at the back of the room a man and a woman in their twenties offer a master class in ironic dancing, disco moving to the heartfelt soleá coming out of the speakers. They are both ungroomed, and wear matching lumberjack shirts and tousled hair and, in spite of their seeming androgyny are flirting shamelessly in full view of everybody.

Eventually we are also ejected and as we near sunrise we are forced to look for a bar that will lift its shutters for us. A Moroccan boy, who had cautioned me against drink in Candela as he sipped from a beer, incongruously becomes our leader, promising entry into a nearby bar owned by a Pakistani friend. It strikes me that Madrid is the only place I know where you will rub elbows with Muslims over a bar counter. The experience is certainly unthinkable in Dublin, where social encounters of this kind seem impossible. There is something intolerably grotesque about the secret bar and it is the final push that I need to make my way to the metro in the company of one of my best friends at eight in the morning.

Eventually we are also ejected and as we near sunrise we are forced to look for a bar that will lift its shutters for us. A Moroccan boy, who had cautioned me against drink in Candela as he sipped from a beer, incongruously becomes our leader, promising entry into a nearby bar owned by a Pakistani friend. It strikes me that Madrid is the only place I know where you will rub elbows with Muslims over a bar counter. The experience is certainly unthinkable in Dublin, where social encounters of this kind seem impossible. There is something intolerably grotesque about the secret bar and it is the final push that I need to make my way to the metro in the company of one of my best friends at eight in the morning.

When I am with this friend I always think of the night he tried to take us to a bar called “Luke, I am your father”. We walked up and down the same street vainly trying to find the bar for about thirty minutes, and I eagerly looked forward to finally locating it, because I was unable to imagine what a place with that name, run by a bunch of kids, as he had said, could look like. Eventually somebody stopped at a doorway, and looking and pointing up, said: “It’s here. It’s closed”. We had passed it a few times and missed it because the name was written in marker on a piece of cardboard clumsily fitted above the sign of the previous bar. The kids who ran it were on holidays or out having fun somewhere else themselves, who knows. Disappointed we moved to our second choice: there someone had brought in an antique bathtub inside the bar you could just barely make out in the dark and a couple of drinkers were enjoying their beers inside it. This place could be better than “Luke, I’m your father”, I thought.

I will never know. I never made it to “Luke, I’m your father” and it closed shortly after. Most bars in Madrid come and go. I will never have nights exactly like that again but I wouldn’t want it any other way. I am alive and this is Madrid, fuck it.

In praise of folly

Last week we had an in service day at work with various activities designed to further our professional and personal horizons, including a healthy eating workshop led by a nutritionist with “a light touch” and an “excellent delivery” in the words of some of the colleagues who attended it. I am afraid I was at an arts and crafts workshop at the time fashioning a Christmas tree ornament shaped like a restive seal aspiring to the condition of a plump bird, painted an ecumenically incongruous shade of watered down duck egg blue, so I missed the talk. Christmas decorations notwithstanding I am disinterested in, even hostile to, nutritional information, so I was highly unlikely to attend. Predictably, the speaker warned the participants of the perils of binge drinking, which is considered to be anything over three glasses of beer. Less predictably, however, this was, for those in attendance, the preface to our Christmas work do and, as an aperitif, it must have left a sour taste. Let’s just say that some of us had to drink more than three glasses of beer to forget just how terrible it is to drink more than three glasses of beer.

This is where I stop to make a disclaimer and apologise for any unintended flippancy in my writing about alcohol: I fully appreciate that alcoholism is a terrible affliction for those who suffer it and their families and friends. I am also aware of the ravages that excessive alcohol consumption causes on the body and, if anybody is in doubt, I recommend Will Self’s inventively terrifying treaty on the matter, Liver, whose short story, “Foie Humain” will put an end to any silly illusions you may have about a portrait in your attic absorbing the brunt of your libations. Further to this, I also know from personal experience that a lot of shite masquerades as deep thinking and heartrending revelation when in thrall to a few jars. But I cannot ignore the little poetry I find in the quotidian, folks, even if this poetry is to be found at the bottom of a highball containing redbull and vodka, so here it is, and may Charles Bukowski forgive me.

Alcohol transfigures: it alters and unlocks faces, loosens limbs, breaks pace, blows wind into sails, it makes us veer, sometimes with catastrophic results, most often though resulting in rough-and-tumble elation or irritation, and very occasionally, opens up an unexpected, although perhaps suspected or intuited, vista of an individual’s inner landscape. It is when I peer into one of these vistas that I appreciate the social value of inebriation and, the evening in question, as I was about to leave my work do, I experienced it from a surprising source.

This source was a fresh faced woman in her twenties: she fleets in and out of the staff room and her sweet smile and peachy complexion belie a discreet and winning disposition to the sardonic. Her sense of irony, given her looks, goes undetected most of the time or is mistaken for mild bonhomie, an interesting complaint, which will go unexplored here. I was about to leave the pub when she extended an arm from the high stool she was sitting on at the bar and cajoled me into staying for another while. It was obvious she had drunk more than usual and although her looks and youth were able to take the burden of alcohol with grace, her manner was altered, assuming that familiarity with strangers that makes spirits so tempting, and occasionally disastrous, at work events. “Don’t go. You remind me of my grandmother,” she said, and I must have registered offense at the suggestion that I was practically octogenarian in my lack of spontaneity and limited stamina, because she hastened to clarify: “You look so much like her. She was a glamorous woman. She had…” here she stumbled to find the right word, “…pedigree”.

This source was a fresh faced woman in her twenties: she fleets in and out of the staff room and her sweet smile and peachy complexion belie a discreet and winning disposition to the sardonic. Her sense of irony, given her looks, goes undetected most of the time or is mistaken for mild bonhomie, an interesting complaint, which will go unexplored here. I was about to leave the pub when she extended an arm from the high stool she was sitting on at the bar and cajoled me into staying for another while. It was obvious she had drunk more than usual and although her looks and youth were able to take the burden of alcohol with grace, her manner was altered, assuming that familiarity with strangers that makes spirits so tempting, and occasionally disastrous, at work events. “Don’t go. You remind me of my grandmother,” she said, and I must have registered offense at the suggestion that I was practically octogenarian in my lack of spontaneity and limited stamina, because she hastened to clarify: “You look so much like her. She was a glamorous woman. She had…” here she stumbled to find the right word, “…pedigree”.

Although the words “glamour” and “pedigree” had never been used to describe me before, it is not vanity that drives me to register them here, but rather her subsequent explanation that she had been taken aback by the similarity for a long time and that, although, long dead, her grandmother had always been an intriguing woman for her: formidable and full of character in her black and white portraits, a woman with backbone and her own ideas; one of those ancestors whose shadow looms large even over those who never knew them in person. As she continued to talk I learnt about her own farming background, her brother’s ideas about what constitutes a good romantic match, and her own attachment to her family, to the dead generations and those very much alive. I cannot claim this woman as my friend, or to have known her from any previous tête-à-têtes, but I can say that, at that moment, she became more human and real to me, yet also more complex and beautiful, like a well-written heroine in a work of fiction. This was, I think, because emboldened by drink, she took the risk of stepping further towards my acquaintance with the kind of observation that a sober person will never reveal for fear of appearing strange. Yet friendship is built on the risks we take to be warmer and deeper to one another and, we must recognise that alcohol, sometimes, gives us a nudge in that direction.

Unfortunately, the intimacy fostered by alcohol is evanescent and the following morning, as I went over to hug her good-bye for the holidays and remind her of our conversation the previous night, she blushed and admitted that, although she remembered she had stopped me on my way out to talk, she could not remember what she had said. “Nothing too embarrassing, I hope,” she added. I told her of course not, walked away, and turning towards her from a distance, wished her a happy Christmas as I left the building.