You are about to read this and you have not watched Some Like It Hot? Get out of here! Do yourself a favour and watch it before you read this, you lucky, lucky, you.

The adjective “hot” has both carnal and gastronomic connotations. For a split second, that salacious poet extraordinaire, Billy Wilder, tries to hoodwink his viewers into thinking that his characters are throwing their spice into their jazz music but you only have to look at Marilyn shimmying behind a tiny ukulele made even tinier by her curves, to realise that every frame here revolves around the compelling presence of human flesh: female flesh to be more precise, even when only a travesty. If ever there was a film that could put its characters in a menu Some Like It Hot is it, and its cracking script barely disguises it.

Wilder has been accused of vulgarity by his detractors because of the occasionally coarse nature of his scenarios and the undercurrent of barely disguised male desire running through his films. It has taken us fifty odd years and seven seasons of Madmen to realise that what passed for crassness in the wane of Wilder’s fame is nothing other than his holding a mirror up to the decade that did untold damage to male livers and women’s self-esteem. You only have to realise that John Fitzgerald Kennedy, that unfettered priapic grotesque, became president of the US only two years after the release of Some Like It Hot to know that Wilder was the Virgil to JFK’s Augustus.

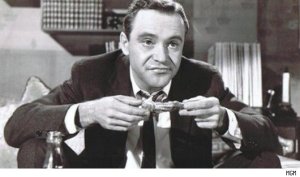

I was watching it again recently and it struck me that beyond its nimble and lovable gender bending antics and its rather sweet and conventional endorsement of romance as a process of acceptance (“Nobody is perfect”, remember?), Some Like It Hot mines sexual harassment for comic gold and continues to get away with it more than fifty years after its release. This is so ever since the camera breaks into the speakeasy where Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon, showcasing the kind of onscreen chemistry that could launch a chain of drugstores as best buddies and jobbing musicians Joe and Jerry, are first seen blowing the sax and plucking the strings of the bow fiddle as they leer at a line of chorus girls wearing the corsety-sequiny swimsuit that passed for music hall attire for any historical period in 1950s American films.

To be fair, shortly after, as he seduces one of the secretaries at a musical agency to borrow her car, we discover that Joe is the kind of “heel” that cheats a dame of her money to bet it on the dog track and then leaves her forlornly staring at a freshly baked pizza pie in her best negligee. I would not say that Wilder endorses this behaviour but rather that he admires the wit and zest required for a “regular Romeo” to keep scoring gullible broads. On his part, Curtis plays Joe with unflappable swagger thus satisfying the high octane drag farce required to elude the mob and the playboy masquerade he concocts to seduce the ditzy Sugar Kane.

Joe and Jerry are two hungry men, no doubt: this is, after all, Chicago in the eve of the Great Depression and they have chosen a life in the lower rungs of bohemia, yet there is little eating in the film even when bread and board are on the cards. No wonder: the moment they see Monroe as Sugar Kowalczyk at the station where they will board the train that will take them to Miami as the unlikely addition to an all female band, Wilder serves us his central metaphor on a silver platter. Two sex starved-men surrounded by goodies they cannot touch, stopped on their tracks by a sashaying Sugar as Jerry, who has been wondering how women manage to walk in high heels and has noticed how “drafty” skirts are, is jolted back into his masculine self by the appearance of Monroe looking like “Jell-o on springs”. Later on, conveniently yet frustratingly disguised as Daphne, he will ogle the blonde “talent” in his new jazz orchestra and describe the dream he used to have as a little boy that one day he would be locked up in his own sweet shop and help himself to all the “cream buns and the mocha éclairs” and the “cherry tarts”. Joe quickly disabuses him of this notion by telling him that he is “on a diet” but it won’t take long for him to have his own designs on the main ingredient at any sweet shop, Sugar.

A 1950s farce with two straight men in drag surrounded by attractive women they lust after would be intolerable in the hands of a lesser director/scriptwriter and would now be largely unwatchable. Wilder and his writing partner I.A.L. Diamond, however, knew that humour, like light, dazzles when it bounces off as many surfaces as it can catch, and this requires multiple perspectives and unexpected directions. In other words, the lusting sugar-crazed child has to become the lusted after “cherry tart” of his dreams and get a taste of what women were doled out on a daily basis in the 1950s: recalcitrant bodily intrusion on the part of strangers, or what was otherwise called “unwanted advances” when women’s bodies were considered a battleground to be conquered and dominated. Thus Daphne, and to a lesser extent, Josephine, experiences the harassment of decrepit millionaires and diminutive bellboys who like them “big and sassy” and therefore gets a taste of his own behaviour as a man. When Jerry complains about this to Joe, he retorts that women are to men what “red flags are to bulls”, to which Jerry, yanking the wig off his head in a telling gesture, replies, “Well, I am tired of being the flag. I want to be the bull again.” Naturally, when it comes to being the pastry or the excitable child that eats it, we all want to be the child.

Wilder does not go as far as to fully embrace his character’s new found empathy for women: after all, it is clear that Jerry does not want to put an end to harassment, he just wants it to stop when he is on the receiving end. After all, he is quick to try a “trick he has learnt on the elevator” on poor Sugar when they are bathing together as pals in the Florida Sea. Nonetheless, Wilder also gives Sugar her own dose of guile and cunning by having her pass herself for a society girl who learnt music in a conservatory and has joined the band for a lark as she tries to seduce Joe as playboy millionaire Junior in yet another twist. When Joe/Junior manages to draw her to the yacht he has “borrowed” from an Osgood head over heels in love with Daphne, he turns the tables once more and pretends he is beyond sex to goad her on. Once more, Wilder continues to exploit his welding of sex and food in a scene where Curtis takes a bite of pheasant to avoid taking a bite of Marilyn. As they get closer and it gets so hot that his glasses “steam up”, Marilyn is shown hovering over Curtis in the position traditionally reserved for the male seducer. I hate to be vulgar but there is no other way to put it: Marilyn is the devourer and she is the one eating Curtis’ face off.

As in real life, hunger banishes the moment love arrives and our characters quickly lose their appetite the moment they fall for each other. Ultimately the film wins its audiences’ heart by recognising that if desire is driven by a perpetual hunger, love is its final satisfaction: the one dish that does not leave you wanting for more. True love only exists when we accept the flawed humanity of our lover: there are many sweets out there but only one sweetheart.